Collections

Introduction

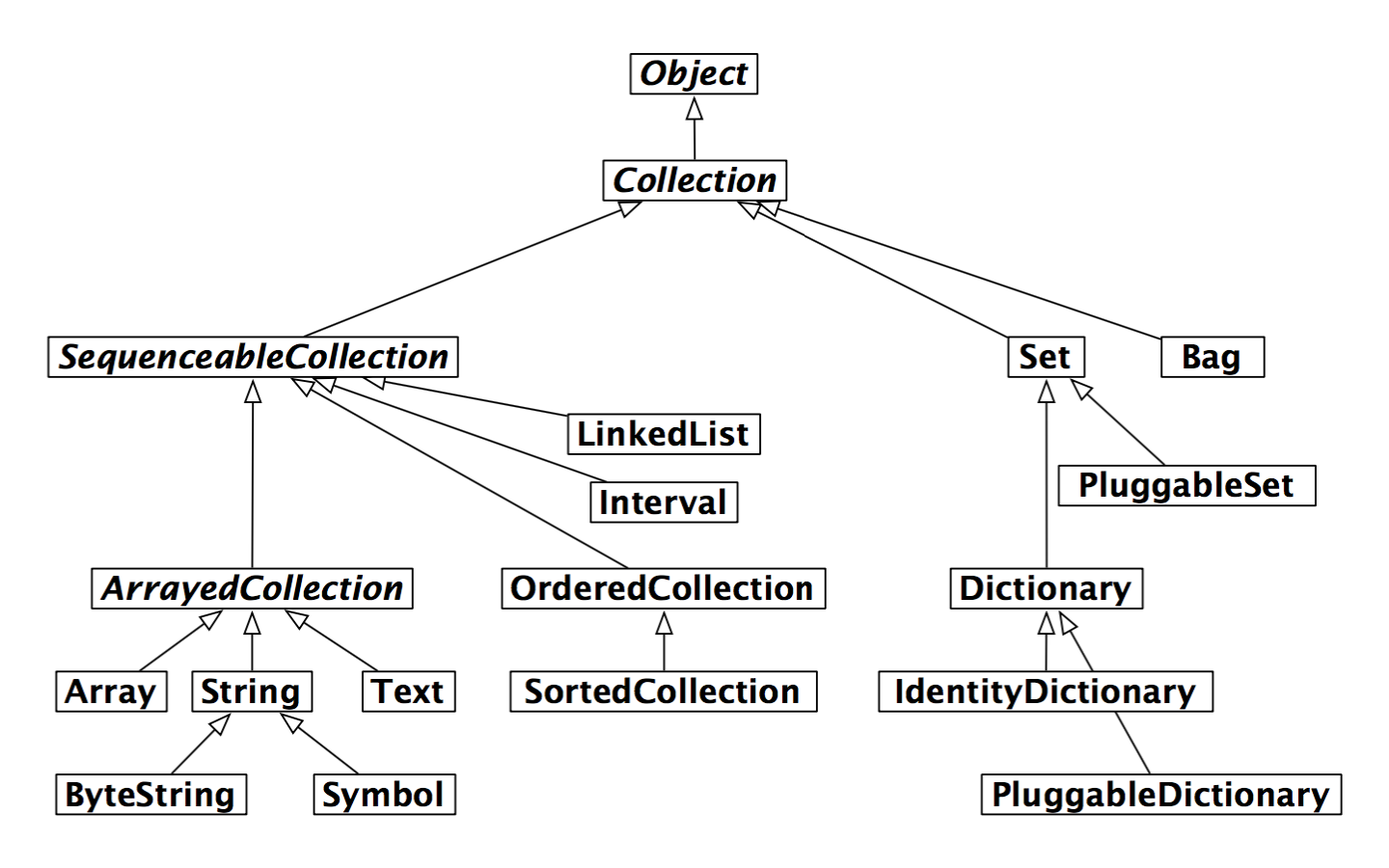

Some of the key collection classes in Pharo

The varieties of collections

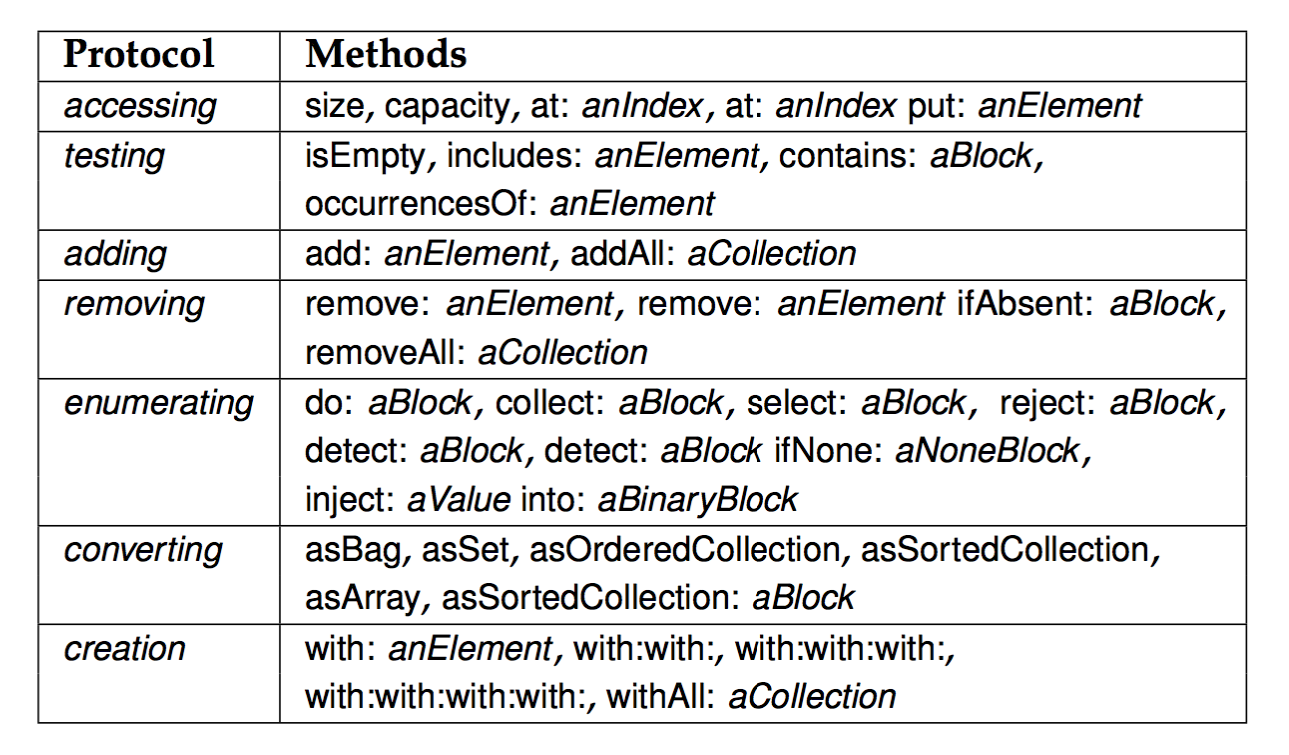

Standard Collection protocols

- Sequenceable: Instances of all subclasses of SequenceableCollection start from a first element and proceed in a well-defined order to a last element. Instances of Set, Bag and Dictionary, on the other hand, are not sequenceable.

- Sortable: A SortedCollection maintains its elements in sort order.

- Indexable: Most sequenceable collections are also indexable, that is, elements can be retrieved with at:. Array is the familiar indexable data structure with a fixed size; anArray at: n retrieves the nth element of anArray, and anArray at: n put: v changes the nth element to v. LinkedLists and SkipList s are sequenceable but not indexable, that is, they understand first and last, but not at:.

- Keyed: Instances of Dictionary and its subclasses are accessed by keys instead of indices.

- Mutable: Most collections are mutable, but Intervals and Symbols are not. An Interval is an immutable collection representing a range of Integers. For example, 5 to: 16 by: 2 is an interval that contains the elements 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15. It is indexable with at:, but cannot be changed with at:put:.

- Growable: Instances of Interval and Array are always of a fixed size.Other kinds of collections (sorted collections, ordered collections, and linked lists) can grow after creation. The class OrderedCollection is more general than Array; the size of an OrderedCollection grows on demand, and it has methods for addFirst: and addLast: as well as at: and at:put:.

- Accepts duplicates: A Set will filter out duplicates, but a Bag will not. Dictionary, Set and Bag use the = method provided by the elements; the Identity variants of these classes use the == method, which tests whether the arguments are the same object, and the Pluggable variants use an arbitrary equivalence relation supplied by the creator of the collection.

- Heterogeneous: Most collections will hold any kind of element.AString , CharacterArray or Symbol, however, only holds Characters. An Array will hold any mix of objects, but a ByteArray only holds Bytes, an IntegerArray only holds Integers and a FloatArray only holds Floats. A LinkedList is constrained to hold elements that conform to the Link |> accessing protocol.

Implementations of collections

| Arrayed Implementation | Ordered Implementation | Hashed Implementation | Linked Implementation | Interval Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array String Symbol | OrderedCollection SortedCollection Text Heap | Set IdentitySet PluggableSet Bag IdentityBag Dictionary IdentityDictionary PluggableDictionary | LinkedList SkipList | Interval |

Some collection classes categorized by implementation technique

- Arrays store their elements in the (indexable) instance variables of the collection object itself; as a consequence, arrays must be of a fixed size, but can be created with a single memory allocation.

- OrderedCollections and SortedCollections store their elements in an array that is referenced by one of the instance variables of the collection. Consequently, the internal array can be replaced with a larger one if the collection grows beyond its storage capacity.

- The various kinds of set and dictionary also reference a subsidiary array for storage, but use the array as a hash table. Bags use a subsidiary Dictionary, with the elements of the bag as keys and the number of occurrences as values.

- LinkedLists use a standard singly-linked representation.

- Intervals are represented by three integers that record the two end points and the step size.

Examples of key classes

We will focus on the most common collection classes: OrderedCollection, Set, SortedCollection, Dictionary, Interval, and Array.

Common creation protocol.

There are several ways to create instances of collections. The most generic ones use the methods new: and with:. new: anInteger creates a collection of size anInteger whose elements will all be nil. with: anObject creates a collection and adds anObject to the created collection. Different collections will realize this behaviour differently. You can create collections with initial elements using the methods with:, with:with: etc. for up to six elements.

Array with: 1 ---> #(1)

Array with: 1 with: 2 ---> #(1 2)

Array with: 1 with: 2 with: 3 ---> #(1 2 3)

Array with: 1 with:2 with:3 with:4 ---> #(1234)

Array with: 1 with:2 with:3 with:4 with:5 ---> #(12345)

Array with: 1 with:2 with:3 with:4 with:5 with:6 ---> #(123456)You can also use addAll: to add all elements of one kind of collection to another kind:

(1 to: 5) asOrderedCollection addAll: '678';

yourself ---> an OrderedCollection(1 2 3 4 5 $6 $7 $8)Take care that addAll: also returns its argument, and not the receiver!

Array

An Array is a fixed-sized collection of elements accessed by integer indices. Contrary to the C convention, the first element of a Smalltalk array is at position 1 and not 0. The main protocol to access array elements is the method at: and at:put:. at: anInteger returns the element at index anInteger. at: anInteger put: anObject puts anObject at index anInteger. Arrays are fixed-size collections therefore we cannot add or remove elements at the end of an array. The following code creates an array of size 5, puts values in the first 3 locations and returns the first element.

anArray:= Array new: 5.

anArray at: 1 put: 4.

anArray at: 2 put: 3/2.

anArray at: 3 put: 'ssss'.

anArray at: 1 ---> 4There are several ways to create instances of the class Array. We can use new:, with:, and the constructs #( ) and { }.

Creation with new: new: anInteger creates an array of size anInteger. Array new: 5 creates an array of size 5.

Creation with with: with: methods allows one to specify the value of the elements. The following code creates an array of three elements consisting of the number 4, the fraction 3/2 and the string ‘lulu’.

Array with: 4 with: 3/2 with: 'lulu' ---> {4 . (3/2) . 'lulu'}Literal creation with #(). #() creates literal arrays with static (or “literal”) elements that have to be known when the expression is compiled, and not when it is executed. The following code creates an array of size 2 where the first element is the (literal) number 1 and the second the (literal) string ‘here’.

#(1 'here') size ---> 2Now, if you evaluate #(1+2), you do not get an array with a single element 3 but instead you get the array #(1 #+ 2) i.e., with three elements: 1, the symbol #+ and the number 2.

#(1+2) ---> #(1 #+ 2)This occurs because the construct #() causes the compiler to interpret literally the expressions contained in the array. The expression is scanned and the resulting elements are fed to a new array. Literal arrays contain numbers, nil, true, false, symbols and strings.

Dynamic creation with { }. Finally, you can create a dynamic array using the construct {}. { a . b } is equivalent to Array with: a with: b. This means in particular that the expressions enclosed by { and } are executed.

{1+2} ---> #(3)

{(1/2) asFloat} at: 1 ---> 0.5

{10 atRandom . 1/3} at: 2 ---> (1/3)Element Access. Elements of all sequenceable collections can be accessed with at: and at:put:.

anArray := #(1 2 3 4 5 6) copy.

anArray at: 3 ---> 3

anArray at: 3 put: 33.

anArray at: 3 ---> 33Be careful with code that modifies literal arrays! The compiler tries to allocate space just once for literal arrays. Unless you copy the array, the second time you evaluate the code your “literal” array may not have the value you expect. (Without cloning, the second time around, the literal #(1 2 3 4 5 6) will actually be #(1 2 33 4 5 6)!) Dynamic arrays do not have this problem.

OrderedCollection

OrderedCollection is one of the collections that can grow, and to which elements can be added sequentially. It offers a variety of methods such as add:, addFirst:, addLast:, and addAll:.

ordCol := OrderedCollection new.

ordCol add: 'Seaside'; add: 'SqueakSource'; addFirst: 'Monticello'.

ordCol ---> an OrderedCollection('Monticello' 'Seaside' 'SqueakSource')Removing Elements. The method remove: anObject removes the first occurrence of an object from the collection. If the collection does not include such an object, it raises an error.

ordCol add: 'Monticello'.

ordCol remove: 'Monticello'.

ordCol ---> an OrderedCollection('Seaside' 'SqueakSource' 'Monticello')Conversion. It is possible to get an OrderedCollection from an Array (or any other collection) by sending the message asOrderedCollection:

#(1 2 3) asOrderedCollection ---> an OrderedCollection(1 2 3)

'hello' asOrderedCollection ---> an OrderedCollection($h $e $l $l $o)Interval

The class Interval represents ranges of numbers. For example, the interval of numbers from 1 to 100 is defined as follows:

Interval from: 1 to: 100 ---> (1 to: 100)The printString of this interval reveals that the class Number provides us with a convenience method called to: to generate intervals:

(Interval from: 1 to: 100) = (1 to: 100) ---> trueWe can use Interval class»from:to:by: or Number»to:by: to specify the step between two numbers as follow:

(Interval from: 1 to: 100 by: 0.5) size ---> 199

(1 to: 100 by: 0.5) at: 198 ---> 99.5

(1/2 to: 54/7 by: 1/3) last ---> (15/2)Dictionary

Dictionaries are important collections whose elements are accessed using keys. Among the most commonly used messages of dictionary you will find at:, at:put:, at:ifAbsent:, keys and values.

colors := Dictionary new.

colors at: #yellow put: Color yellow.

colors at: #blue put: Color blue.

colors at: #red put: Color red.

colors at: #yellow ---> Color yellow

colors keys ---> a Set(#blue #yellow #red)

colors values ---> {Color blue . Color yellow . Color red}IdentityDictionary

While a dictionary uses the result of the messages = and hash to determine if two keys are the same, the class IdentityDictionary uses the identity (message ==) of the key instead of its values, i.e., it considers two keys to be equal only if they are the same object.

Set

The class Set is a collection which behaves as a mathematical set, i.e., as a collection with no duplicate elements and without any order. In a Set elements are added using the message add: and they cannot be accessed using the message at:. Objects put in a set should implement the methods hash and =.

s := Set new.

s add: 4/2; add: 4; add:2. ssize ---> 2SortedCollection

In contrast to an OrderedCollection, a SortedCollection maintains its elements in sort order. By default, a sorted collection uses the message <= to establish sort order, so it can sort instances of subclasses of the abstract class Magnitude, which defines the protocol of comparable objects (<, =, >, >=, between:and:…).

You can create a SortedCollection by creating a new instance and adding elements to it:

SortedCollection new add: 5; add: 2; add: 50; add: −10; yourself.

---> a SortedCollection(−10 2 5 50)FAQ: How do you sort a collection?

ANSWER: Send the message asSortedCollection to it.

String

A Smalltalk String represents a collection of Characters. It is sequenceable, indexable, mutable and homogeneous, containing only Character instances. Like Arrays, Strings have a dedicated syntax, and are normally created by directly specifying a String literal within single quotes, but the usual collection creation methods will work as well.

'Hello' ---> 'Hello'

String with: $A ---> 'A'

String with: $h with: $i with: $! ---> 'hi!'

String newFrom: #($h " $l $l $o) ---> 'hello'String matching. It is possible to ask whether a pattern matches a string by sending the match: message. The pattern can specify * to match an arbitrary series of characters and # to match a single character. Note that match: is sent to the pattern and not the string to be matched.

'GNU/Linux mag' findString: 'Linux' ---> true

'GNU/Linux #ag' match: 'GNU/Linux tag' ---> true

Another useful method is findString:.'GNU/Linux mag' findString: 'Linux' ---> 5

'GNU/Linux mag' findString: 'linux' startingAt: 1 caseSensitive: false ---> 5Some tests on strings. The following examples illustrate the use of isEmpty, includes: and anySatisfy: which are further messages defined not only on Strings but more generally on collections.

'Hello' isEmpty ---> false

'Hello' includes: $a ---> false

'JOE' anySatisfy: [:c | c isLowercase] ---> false

'Joe' anySatisfy: [:c | c isLowercase] ---> trueString templating. There are three messages that are useful to manage string templating: format:, expandMacros and expandMacrosWith:.

'{1} is {2}' format: {'Pharo' . 'cool'} ---> 'Pharo is cool'Some other utility methods. The class String offers numerous other utilities including the messages asLowercase, asUppercase and capitalized.

'XYZ' asLowercase ---> 'xyz'

'xyz' asUppercase ---> 'XYZ'

'hilaire' capitalized ---> 'Hilaire'

'1.54' asNumber ---> 1.54

'this sentence is without a doubt far too long' contractTo: 20 ≠æ 'this sent...too long'Note that there is generally a difference between asking an object its string representation by sending the message printString and converting it to a string by sending the message asString. Here is an example of the difference.

#ASymbol printString ---> '#ASymbol'

#ASymbol asString ---> 'ASymbol'A symbol is similar to a string but is guaranteed to be globally unique. For this reason symbols are preferred to strings as keys for dictionaries, in particular for instances of IdentityDictionary.

Collection iterators

Iterating (do:)

The method do: is the basic collection iterator. It applies its argument (a block taking a single argument) to each element of the receiver. The following example prints all the strings contained in the receiver to the transcript.

#('bob' 'joe' 'toto') do: [:each | Transcript show: each; cr].

Variants. There are a lot of variants of do:, such as do:without:, doWithIndex: and reverseDo:: For the indexed collections (Array, OrderedCollection, SortedCollection) the method doWithIndex: also gives access to the current index. This method is related to to:do: which is defined in class Number.

#('bob' 'joe' 'toto') doWithIndex: [:each :i | (each = 'joe') ifTrue: [ ø i ] ] ---> 2

For ordered collections, reverseDo: walks the collection in the reverse order.

The following code shows an interesting message: do:separatedBy: which executes the second block only in between two elements.

res := ''.

#('bob' 'joe' 'toto') do: [:e | res := res, e ] separatedBy: [res := res, '.'].

res ---> 'bob.joe.toto'

Note that this code is not especially efficient since it creates intermediate strings and it would be better to use a write stream to buffer the result:

String streamContents: [:stream | #('bob' 'joe' 'toto') asStringOn: stream delimiter: '.' ]

---> 'bob.joe.toto'

Dictionaries. When the message do: is sent to a dictionary, the elements taken into account are the values, not the associations. The proper methods to use are keysDo:, valuesDo:, and associationsDo:, which iterate respectively on keys, values or associations.

Collecting results (collect:)

If you want to process the elements of a collection and produce a new collection as a result, rather than using do:, you are probably better off using collect:, or one of the other iterator methods. Most of these can be found in the enumerating protocol of Collection and its subclasses.

Imagine that we want a collection containing the doubles of the elements in another collection. Using the method do: we must write the following:

double := OrderedCollection new.

#(1 2 3 4 5 6) do: [:e | double add: 2 * e].

double ---> an OrderedCollection(2 4 6 8 10 12)Selecting and rejecting elements

select: returns the elements of the receiver that satisfy a particular condition:

(2 to: 20) select: [:each | each isPrime] ≠æ #(2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19)

reject: does the opposite:

(2to:20)reject:[:each|eachisPrime] ---> #(468910121415161820)

Identifying an element with detect:

The method detect: returns the first element of the receiver that matches block argument.

'through' detect: [:each | each isVowel] ---> $o

The method detect:ifNone: is a variant of the method detect:. Its second block is evaluated when there is no element matching the block.

Smalltalk allClasses detect: [:each | '*cobol*' match: each asString] ifNone: [ nil ] ---> nil

Accumulating results with inject:into:

Functional programming languages often provide a higher-order function called fold or reduce to accumulate a result by applying some binary operator iteratively over all elements of a collection. In Pharo this is done by Collection» inject:into:.

The first argument is an initial value, and the second argument is a two- argument block which is applied to the result this far, and each element in turn.

A trivial application of inject:into: is to produce the sum of a collection of numbers. Following Gauss, in Pharo we could write this expression to sum the first 100 integers:

(1 to: 100) inject: 0 into: [:sum :each | sum + each ] ---> 5050

Other messages

count: The message count: returns the number of elements satisfying a condition. The condition is represented as a boolean block.

Smalltalk allClasses count: [:each | 'Collection*' match: each asString ] ---> 3

includes: The message includes: checks whether the argument is contained in the collection.

colors := {Color white . Color yellow. Color red . Color blue . Color orange}. colors includes: Color blue. ---> true

anySatisfy: The message anySatisfy: answers true if at least one element of the collection satisfies the condition represented by the argument.

colors anySatisfy: [:c | c red > 0.5] ---> true

Some hints for using collections

A common mistake with add: The following error is one of the most frequent Smalltalk mistakes.

collection := OrderedCollection new add: 1; add: 2. collection ---> 2

Here the variable collection does not hold the newly created collection but rather the last number added. This is because the method add: returns the element added and not the receiver.

The following code yields the expected result:

collection := OrderedCollection new. collection add: 1; add: 2.

collection ≠æ an OrderedCollection(1 2)

You can also use the message yourself to return the receiver of a cascade of messages:

collection := OrderedCollection new add: 1; add: 2; yourself ---> an OrderedCollection(1 2)

Removing an element of the collection you are iterating on. Another mistake you may make is to remove an element from a collection you are currently iterating over. remove:

range := (2 to: 20) asOrderedCollection.

range do: [:aNumber | aNumber isPrime ifFalse: [ range remove: aNumber ] ].

range ---> an OrderedCollection(2 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19)This result is clearly incorrect since 9 and 15 should have been filtered out! The solution is to copy the collection before going over it.

range := (2 to: 20) asOrderedCollection.

range copy do: [:aNumber | aNumber isPrime ifFalse: [ range remove: aNumber ] ].

range ---> an OrderedCollection(2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19)Redefining both = and hash. A difficult error to spot is when you redefine = but not hash. The symptoms are that you will lose elements that you put in sets or other strange behaviour. One solution proposed by Kent Beck is to use xor: to redefine hash. Suppose that we want two books to be considered equal if their titles and authors are the same. Then we would redefine not only = but also hash as follows:

Redefining = and hash

Book >>

aBook

self.class = aBook class ifFalse: [^ false].

^ title = aBook title and: [ authors = aBook authors]

Book >>

hash

^ title hash xor: authors hashChapter summary

The Smalltalk collection hierarchy provides a common vocabulary for uniformly manipulating a variety of different kinds of collections.

- A key distinction is between SequenceableCollections, which maintain their elements in a given order, Dictionary and its subclasses, which maintain key-to-value associations, and Sets and Bags, which are unordered.

- You can convert most collections to another kind of collection by sending them the messages asArray, asOrderedCollection etc..

- To sort a collection, send it the message asSortedCollection.

- Literal Arrays are created with the special syntax #( … ). Dynamic Arrays are created with the syntax { … }.

- A Dictionary compares keys by equality. It is most useful when keys are instances of String. An IdentityDictionary instead uses object identity to compare keys. It is more suitable when Symbols are used as keys, or when mapping object references to values.

- Strings also understand the usual collection messages. In addition, a String supports a simple form of pattern-matching. For more advanced application, look instead at the RegEx package.

- The basic iteration message is do:. It is useful for imperative code, such as modifying each element of a collection, or sending each element a message.

- Instead of using do:, it is more common to use collect:, select:, reject:, includes:, inject:into: and other higher-level messages to process collections in a uniform way.

- Never remove an element from a collection you are iterating over. If you must modify it, iterate over a copy instead.

- If you override =, remember to override hash as well!